1. Introduction

Design, as a formalised industry, has relied on systems since as early as the 1970s - from NASA’s 1975 Graphics Standards Manual [1] to Google’s material UI [2] in 2014 and beyond.

To manage the increasing complexity of digital products, the industry's primary reflex has been to define the digital matter of our screens in order to streamline our own workflows. This systemisation of digital components [3], however, was a catalyst for design’s demise hidden in plain sight. By treating interfaces and their components as Newtonian absolutes (ie: assuming properties remain unchanged regardless of the forces acting upon them) we successfully defined the matter of our digital universe at the cost of a relative frame of reference.

As human-technology interaction evolves beyond the speed of our comprehension, knowing what the elements are, how they interact, or the scenarios in which they are used, is no longer enough to outpace the velocity of our own inventions. To accommodate the shifting, real-time forces of user context, environment and intent, we must evolve our workflow beyond the static constraints of categorisation and engineer the determination of interfaces that respond to the forces at play.

The interfaces of the future cannot be built with the components of the past. Atoms are too static. Systems are too rigid. User interfaces are now a physics problem, requiring a new set of laws.

2. Quantifying Subjective Forces

A generative digital ecosystem in this sense is one capable of self-assessing state & presenting an adaptive UI layer to the user accordingly. To do this, the system must first quantify its current state, in order to determine whether a phase change is required.

Digital General Relativity

To quantify subjective forces, this protocol relies on the theory of Digital General Relativity. In the physical universe, mass dictates the curvature of spacetime [4]. In the digital universe, we postulate that Context acts as Mass, dictating the curvature of the interface and forces acting upon it, relative to other digital masses.

A high-risk, high-value context possesses immense ‘Mass’, curving the digital environment around it, forcing the compression of user interfaces into rigid, dense structures. Conversely, low-risk contexts possess negligible mass, creating a flat spacetime where elements can drift with high entropy.

Therefore, to engineer and govern generative systems, we must first quantify the Mass of the context by measuring the gravitational and thermodynamic constants. Let’s define the six independent variables (micro-parameters) that will act as the forces of our digital universe. They are the raw, observable and measurable data points.

Resistance variables: System constraints

These forces generate Pressure. They represent the Mass of the object and its environment.

1. Gravity

Gravity in digital systems can be considered not only as the importance of ‘the thing’, it can be considered the measurable curvature of the interface created by the consequence of error. Or, more simply, the ‘cost’ to the user associated with use of the system or feature.

Metric: Operational Risk Score (0–100) + User Consequence

2. Friction

The resistance a mass exerts against motion. This represents the energy cost to move an object or, perform a single action.

Metric: Interaction Cost (Time to Complete) + Element Density

3. Load

The volume of data objects currently held in the active state. The variable weight of the data itself. The magnitude of the active dataset held in memory or transit. A high load requires a stronger state to support it without collapse.

Metric: Data Payload Weight + Object Complexity

Energy variables: Human context

These forces generate Temperature. They represent the energy a user is injecting into a system in order to use it.

4. Velocity

The rate of intent execution. Rapid movement generates heat. If Velocity exceeds the system’s ability to shed heat, or the expected output is a high-heat environment, the interface must transition to a higher energy state to reduce friction.

Metric: Interactions per Second / Context Multiplier

5. Volatility

Navigational erraticism. In thermodynamics, chaos is universally heating. Whether you are playing a game or doing your taxes, if you are rapidly reversing direction, you are thrashing.

Metric: Rate of navigational reversal (thrashing)

6. Force (Demand)

The magnitude of external user pressure on a system. Massive concurrent user demand compresses the system, forcing it into a survival state.

Metric: Active Concurrent Users / System Capacity

3. Applied Thermodynamics: Pressure and Temperature

In thermodynamics, changes in pressure and/or temperature affect the entropy of a system. The order or disorder of the atoms based on the availability of energy to keep them ordered, or conversely, disperse them chaotically. Measurement of the 6 variables in section 2 are converted into scalar measurements used to calculate our two state variables (macro-parameters):

Pressure (P)

Pressure in our context, it is the sum of compressive forces acting upon a system. It is the weighted sum of the Resistance Variables in Section 2.

Temperature (T)

Temperature represents the heat generated by the users interaction with the system. It is calculated as an aggregate of the Energy Variables in Section 2.

4. Determining States

Phase determination

The protocol feeds the calculated Pressure and Temperature into our Phase Determination Function using the following calculation:

The Physics Engine plots the Pressure (P) and Temperature (T) coordinates against our proprietary phase-boundary thresholds.

• If P overwhelmingly dominates T, the system solidifies.

• If T increases, melting the structural friction, it flows into a Liquid or sublimates into a Gas.

• If both P and T cross the critical event horizon (extreme risk + extreme demand), the system reaches a ‘critical mass’ and effectively ionises into a Plasma state.

Developers can simply pass the context variables to the physics engine in order for the protocol to determine the phase state. A user interface is no longer chosen, it emerges.

Elemental States

Note: The below states are outline only, and the subject of an ongoing community effort to align and build upon these guidelines.

Solid

High inertia, high constraint. Low entropy, low energy.

Predictable & safe interfaces. Structured clear elements. Functional. Error prevention.

Use Case: Banking ledgers, transport controls, medical records, setting foundational configuration.

Liquid

Flow state. Balanced entropy, medium constraint, medium energy.

Remove friction for high-frequency tasks.

Use Case: Social feeds, project management boards, email clients, checkout flows.

Gas

High entropy, high energy, low inertia, low constraint.

Allow expansion and connection. Free and changing interfaces. Experimental interactions.

Use Case: Digital whiteboards, search engines, creative writing tools.

Plasma

Critical mass. Extreme energy, extreme constraint.

Focus on containment & observability. Immediately manage chaos before catastrophic consequence.

Use Case: Incident response dashboards, server outage terminals, stock trading during a crash.

5. Implementation: Governing the Ecosystem

To prove the viability of Digital General Relativity in a production environment, we engineered th3makr - a client-side physics engine built to execute the Phase State Protocol.

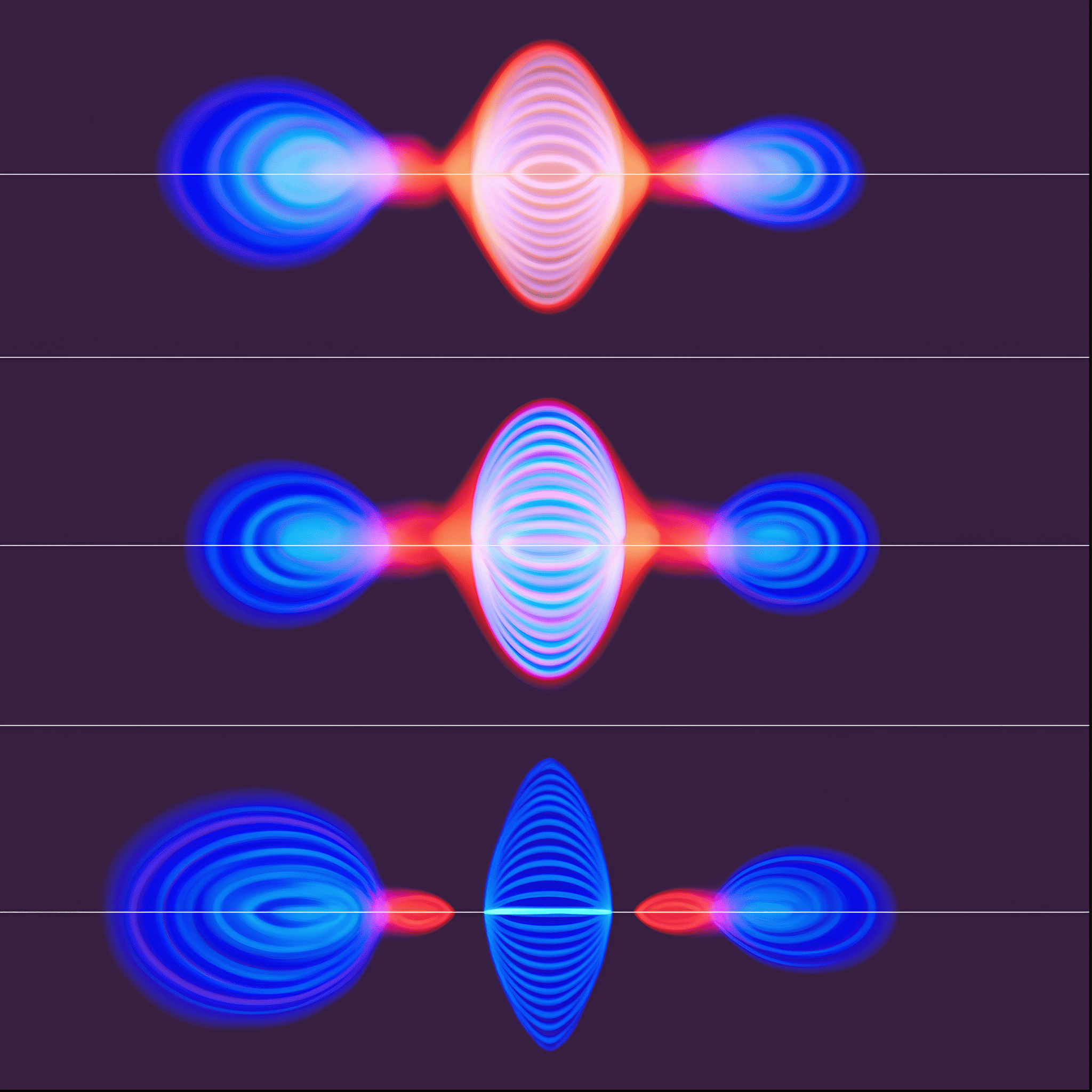

Experiment 01: The Map

Blue: Raw Input | Pink: Hysteresis Buffer (System State)

Experiment 02: Deterministic Transformation

Architecturally, the engine operates independently of the UI framework. It functions as a middleware provider that intercepts environmental data, calculates the physics, and broadcasts the thermodynamic state to the rendering layer.

The Thermodynamic Schema

Before rendering, the ecosystem requires a baseline definition of its relative spacetime. This is provided via a JSON schema, which can be authored manually or generated instantly by an LLM based on business context - use the tools at phasestate.io to get started on schema experimentation. The schema dictates the base physics and the tokenised outputs for each state. This also generates the Natural State of the Digital Mass or Object - ie: the digital product being created if generative technology is used to do so from inception.

{

"context": { "domain": "FinTech", "riskLevel": "high" },

"physics": { "basePressure": 4.5, "baseTemperature": 1.2 },

"states": {

"SOLID": { "density": "compact", "minImportance": 0 },

"LIQUID": { "density": "normal", "minImportance": 30 },

"GAS": { "density": "expansive", "minImportance": 60 },

"PLASMA": { "density": "brutalist", "minImportance": 90 }

}

}The Physics Engine

As the user interacts with the system, environmental sensors continuously feed micro-parameters (Gravity, Friction, Load, Velocity, Volatility, Force) into the engine.

The engine calculates the real-time Pressure and Temperature by averaging the Resistance and Energy variables. However, to prevent UI thrashing - a disorienting phenomenon in early tests, where an interface flickers rapidly between states due to micro-fluctuations in user input - the engine employs a ‘Hysteresis Buffer’. This mimics properties of the physical universe; water does not instantaneously freeze into ice or boil into vapour, there is a natural delay. This buffer can be contextualised, or even turned off altogether to control when/where phase change occurs.

// Theoretical Phase Determination with Hysteresis

const BUFFER = 1.5;

function determinePhase(temperature, pressure, currentPhase) {

// Escaping a high-intensity state requires dropping below the buffer threshold

if (currentPhase === 'GAS' && temperature > (5 - BUFFER)) return 'GAS';

if (currentPhase === 'SOLID' && pressure > (5 - BUFFER)) return 'SOLID';

if (currentPhase === 'PLASMA' && (pressure > (5 - BUFFER) || temperature > (5 - BUFFER))) return 'PLASMA';

// Entering a new state requires breaking the threshold

if (pressure <= 5 && temperature <= 5) return 'LIQUID';

if (pressure > 5 && temperature <= 5) return 'SOLID';

if (pressure <= 5 && temperature > 5) return 'GAS';

return 'PLASMA';

}The Provider and Component Guardians

The ecosystem's state is managed by a centralised provider. The provider merges the `basePressure` of the environment (from the schema) with the real-time `sensorPressure` from the user.

Individual UI components no longer dictate their own styling. Instead, they are wrapped in "Guard" components that declare their relative contextual importance (mass). When the engine calculates a phase shift, the Guard receives the new state tokens (e.g., density: "compact") and instantaneously reconstructs the UI to either determine interface generation or survive a new physical environment.

This unidirectional flow decouples the design of the interface from the logic of its survival.

6. Implications and a shift in UI economics

“Wait, do I have to do quadruple the work and design/build four states for everything now?”

The short answer is no. The Phase State Protocol alters the economics of digital product design & delivery. Typically, to ensure system survival across a plethora of scenarios, design, product and engineering teams are required to hardcode bespoke logic, complex state management and multiple breakpoint combinations. This approach incurs huge technical debt from the outset.

By shifting to a physics-based approach, we are separating the UI from hard-coded or conditional logic. Designers no longer need to manually create hundreds of screens or component variations depicting every scenario imaginable. Engineers are no longer required to write and maintain state-management code or cater for seemingly infinite edge-cases.

Instead, by establishing this thermodynamic schema, teams unlock multiple advantages:

- The schema acts as the ultimate contextual prompt, an LLM can parse this thermodynamic blueprint to instantly compile and generate a fully-formed interface from zero. This bypasses the need for human-authored UI components, while guaranteeing a mathematically and contextually optimised product.

- Once deployed, the physics engine natively determines the exact state required for survival and passes it to the UI layer. This works to prevent catastrophic interface failures in high-stress user scenarios by automatically shedding weight to survive, allowing complex ecosystems to scale without a corresponding increase in engineering overhead.

7. The Future

The Phase State Protocol was engineered as a solution to the transitional constraints of the current web, but its true implications lie in the multi-dimensional interface concepts of the future. As digital ecosystems expand into automotive dashboards, industrial IoT, and spatial environments (AR/VR), hardcoded responsive design becomes obsolete.

Consider an interface used to control a spacecraft. The digital thermodynamic forces at play during takeoff (extreme gravity, and extreme velocity - the digital versions being almost 1:1 representations of the physical ones in this example) are vastly different from cruising through the vacuum of space (low gravity, low volatility), or manually docking with a station (high friction, high load).

A static design system would require an astronaut to navigate menus to find the required functions for each scenario. A Generative Digital Ecosystem, governed by the Phase State Protocol, simply measures the digital telemetry and presents the naturally occurring set of controls. As the ship enters the atmosphere of another planet, the external pressure (yes, physical and digital in this example) and velocity spike, causing the interface to autonomously phase-shift from Liquid to Solid, or even Plasma - especially in a scenario that requires stripping away all non-essential data and rendering only the critical controls required for UI and human survival.

By removing the cognitive burden of navigating an interface, the protocol allows humans to focus entirely on task (or goal). Whether applied to a spacecraft, self-driving vehicles in a storm, or trading floor terminals during a market crash, the protocol ensures the digital interface naturally supports the thermodynamic reality of the moment.

8. Conclusion

We have proposed and proven a protocol for determining the state of a generative UI within all manner of digital ecosystems, from zero-to-one creation, to measuring micro-interactions at a feature-level, application states or even suites of applications across global networks.

The systemisation of the design process over recent decades was merely the pile of wood in the fireplace. The burning match was the unprecedented velocity at which generative computing technologies have advanced. The alignment of our design determination logic with that of statistical mechanics was therefore, simply an inevitability [5].

The autonomous nature of universal physics is, quite naturally, required in the digital space at an algorithmic level if we are to progress our thinking, and our industry’s potential, past its current static constraints.

The digital ecosystem designers of the future will not design elements; they will design the invisible forces in-between.